In an era dominated by digital screens and instant notifications, the tactile experience of flipping through a newspaper might seem archaic. Yet, the humble material that forms the backbone of this centuries-old tradition—newsprint paper—remains a marvel of engineering, economics, and environmental science. How does this unassuming paper, often dismissed as "low quality," sustain the global circulation of newspapers, books, and even packaging? What secrets lie in its rough texture and grayish hue? This deep dive into newsprint paper explores its history, production, environmental impact, and enduring relevance in a world racing toward digitization.

1. The Birth of Newsprint: A Historical Perspective

From Rag to Wood Pulp

Newsprint’s origins are intertwined with the rise of mass media. Before the 19th century, paper was primarily made from cotton rags, a labor-intensive and expensive process. The invention of the steam-powered printing press in 1814 by Friedrich Koenig revolutionized publishing but exposed a critical bottleneck: the lack of affordable paper. Enter mechanical wood pulp—a breakthrough in the mid-1800s that replaced rags with groundwood. By pulping softwood trees like spruce and pine, manufacturers could produce paper at scale, slashing costs and democratizing access to printed information.

The Newspaper Boom

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw newspapers proliferate globally, driven by urbanization and rising literacy. Newsprint became synonymous with daily life, enabling titans like The New York Times and The Times of London to reach millions. However, this boom came at a cost: early newsprint was brittle, prone to yellowing, and environmentally destructive due to unsustainable logging practices.

Key Innovations

-

Sulfite Process (1870s): Chemical pulping improved paper strength by removing lignin, a polymer that causes yellowing.

-

Recycled Fiber Integration (1920s): To reduce waste, mills began blending recycled paper into newsprint.

-

Alkaline Sizing (1980s): Modern additives enhanced printability and reduced ink bleed.

2. Anatomy of Newsprint: Materials and Manufacturing

Raw Materials: More Than Just Trees

Contrary to popular belief, newsprint isn’t made solely from virgin wood. A typical mix includes:

-

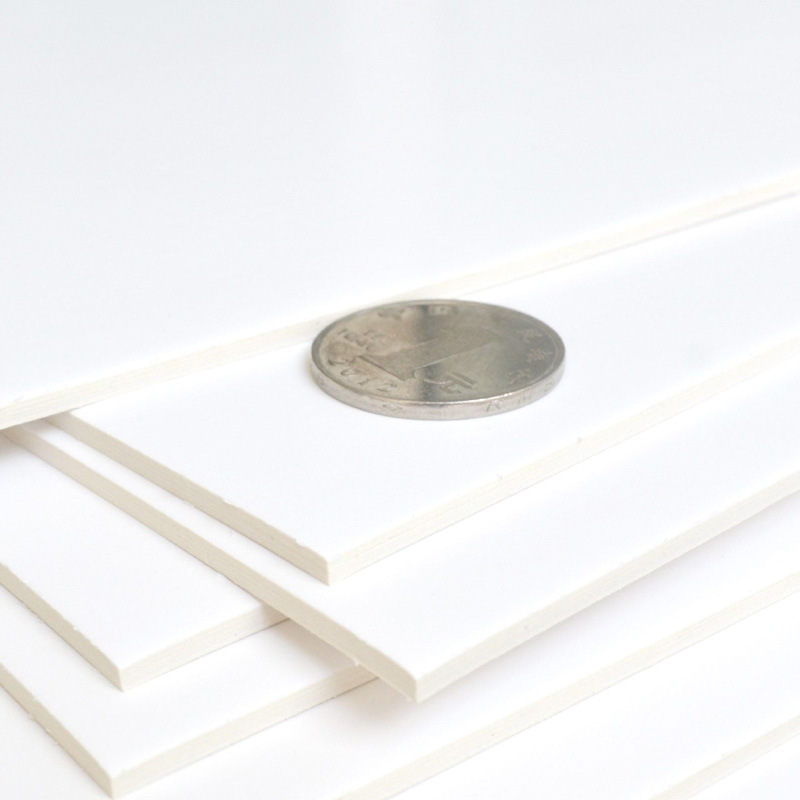

60–70% Mechanical Pulp: Provides bulk and opacity.

-

20–30% Recycled Fiber: Reduces costs and environmental impact.

-

10% Chemical Pulp (e.g., kraft): Adds tensile strength.

The Manufacturing Process

-

Debarking and Chipping: Logs are stripped and chipped into 1–2 cm pieces.

-

Mechanical Pulping: Chips are ground into fibers using stone or steel plates. This method retains most lignin, explaining newsprint’s gray color.

-

Bleaching (Optional): Hydrogen peroxide brightens the pulp minimally to preserve affordability.

-

Paper Machine: The pulp slurry is sprayed onto a moving mesh, pressed, dried, and rolled into giant reels.

-

Finishing: Rolls are cut into sheets or left intact for high-speed printing presses.

Why Is Newsprint So Cheap?

-

Low-Quality Fiber: Short, lignin-rich fibers reduce production costs.

-

High-Speed Production: Modern paper machines operate at 60–100 km/h, minimizing labor expenses.

-

Economies of Scale: Global demand (over 20 million metric tons annually) keeps prices competitive.

3. Environmental Footprint: Myths and Realities

The Deforestation Debate

Critics often blame newsprint for forest degradation, but the reality is nuanced. In Scandinavia and Canada—key producers—forests are managed sustainably, with strict replanting laws. For every tree harvested, 3–4 saplings are planted. Moreover, newsprint relies on "low-value" trees unsuitable for lumber, reducing waste.

Carbon Emissions and Energy Use

Producing 1 ton of newsprint emits ~900 kg of CO₂, comparable to copy paper. However, recycling offsets this significantly:

-

Recycling 1 ton saves 17 trees, 4,000 kWh of energy, and 26,000 liters of water.

-

Over 70% of newsprint in the EU and North America is recycled, compared to <50% for packaging.

The Recycling Challenge

Newsprint fibers shorten with each reuse, limiting their lifecycle to 5–7 cycles. Innovations like enzyme treatment and de-inking advancements aim to extend fiber usability. Meanwhile, "closed-loop" mills integrate recycled content directly into new production.

Alternatives on the Horizon

-

Agricultural Residues: Wheat straw and bagasse (sugarcane waste) are emerging as pulp sources.

-

Synthetic Newsprint: Waterproof polymer-based papers are tested for outdoor use.

4. The Digital Age: Is Newsprint Obsolete?

Decline vs. Resilience

Global newsprint consumption has halved since 2000, driven by online media. Yet niche markets thrive:

-

Emerging Economies: India and Africa see rising demand due to low internet penetration.

-

Specialty Print: Community newspapers, event programs, and book publishing still favor newsprint’s cost-effectiveness.

Unexpected Applications

-

Packaging: E-commerce companies use newsprint for void fill and wrapping.

-

Composting: Its biodegradability makes it ideal for garden mulch.

-

Art and Craft: Artists prize its absorbency for charcoal and ink sketches.

The Nostalgia Factor

Surveys show 65% of readers prefer physical newspapers for in-depth reading. Publishers like The Guardian now offer hybrid subscriptions, blending digital access with weekend print editions.

5. The Future: Reinventing Newsprint for Sustainability

Circular Economy Models

Mills are adopting zero-waste strategies:

-

Sludge-to-Energy: Waste sludge is burned to power production.

-

Biorefineries: Extract lignin for biofuels and vanillin flavoring.

Smart Newsprint

Researchers are embedding QR codes and NFC chips into paper, bridging print and digital. Imagine scanning a newsprint ad to unlock a video demo!

Policy and Consumer Role

-

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR): Laws in the EU mandate recycling quotas for publishers.

-

Consumer Awareness: Choosing recycled newsprint supports green jobs and reduces landfill waste.

English

English عربى

عربى Español

Español